Theory A / Theory B

People naturally seek to understand their world and develop explanations based on their experiences. When these beliefs are inaccurate or only partially correct, they can lead to behaviors that unintentionally reinforce the original belief. A key early task in therapy is for the therapist and client to collaborate on understanding the client’s difficulties, often through case formulation. The theory A theory B technique provides a non-confrontational way to help clients explore alternative interpretations of their problems, guiding the process of gathering evidence to test these views. The worksheet leads therapists and clients through a structured process of describing and evaluating different explanations for the client’s experiences, and includes three case examples to demonstrate its application across various clinical presentations.

Download or send

Related resources

Tags

Languages this resource is available in

Problems this resource might be used to address

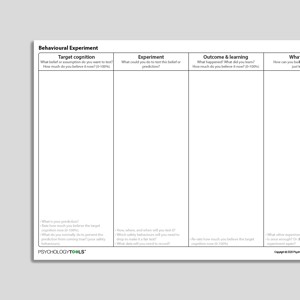

Techniques associated with this resource

Introduction & Theoretical Background

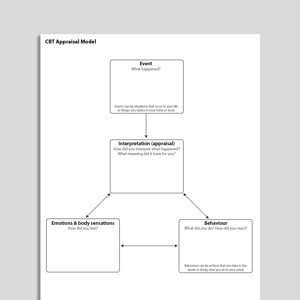

People actively try to understand their world and what happens to them by developing explanations based upon their experiences. Clients who are struggling with mental health problems will typically hold beliefs that explain their observations. These beliefs are often inaccurate or partial understandings of their experiences, and they can lead to behaviors that unintentionally prolong or reinforce the original belief. For example:

- A client with panic disorder believes that her racing heart indicates an imminent heart attack. She stops exercising, reducing opportunities to learn that her heart is healthy and can beat quickly without failing.

- A client with OCD believes that his intrusive thoughts of children mean that he is a paedophile. He tries to suppress his thoughts, which leads to more intrusions (a phenomenon known as the ‘rebound effect’) and makes them even harder to control. Avoiding children also heightens the emotional significance of these encounters when they

Therapist Guidance

"Most people come to therapy with an explanation or ‘theory’ about their experiences. It seems like your understanding is <client’s belief – ‘Theory A’>, which is based on the reasons you described earlier. Given your understanding, it makes sense that you have found yourself using these safety behaviors or coping strategies. CBT is a kind of therapy which is grounded in science, so I’d like us to be like scientists when we explore beliefs. I’ve worked with other people who had similar problems to yours, and I’d like to suggest the possibility of a different perspective that we can explore together."

This technique can be used when clients hold problematic beliefs about their experiences (Theory A), such as believing these experiences indicate there is a threat to themselves or others. The therapist introduces the idea that there might be an alternative explanation or hypothesis (Theory B).

Helpful analogies include those

References And Further Reading

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., Emery, G., DeRubeis, R. J., & Hollon, S. D. (2024). Cognitive therapy of depression (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Freeman, D. (2024). Developing psychological treatments for psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 224(5), 147–149. doi:10.1192/bjp.2024.5

- Gregory, J., & Foster, C. (2023). Session-by-session change in misophonia: a descriptive case study using intensive CBT. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 16, e18.

- Gústavsson, S. M., Salkovskis, P. M., & Sigurðsson, J. F. (2021). Cognitive analysis of specific threat beliefs and safety-seeking behaviours in generalised anxiety disorder: Revisiting the cognitive theory of anxiety disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 49, 526-539. DOI: 10.1017/S135246582100014X.

- Lambie, J. (2014). How to be critically open-minded: a psychological and historical analysis. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Salkovskis, P. M. (1989). Somatic problems. In: K. Hawton, P. M. Salkovskis, J. Kirk, & D. M. Clark (Eds.), Cognitive behaviour therapy for psychiatric problems: A practical guide (pp.