Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Obsessions are unwanted thoughts and images that pop into your mind which you find unacceptable, or which make you feel anxious. Compulsions are things that you do in response to your obsessions, often to stop harm from occurring, or just to make you feel better. People who experience obsessions and compulsions to a level that interferes significantly with their life are said to have obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and it is thought that between 1 and 2 people out of every 100 experience OCD every year [1]. Fortunately, there are some effective psychological treatments for OCD including Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP).

What is OCD?

Obsessive compulsive disorder is often misunderstood. You might have heard people refer to themselves as ‘being OCD’ if they like things to be arranged ‘just so’, but in fact obsessive compulsive disorder is about suffering from ‘obsessions’ and ‘compulsions’. These words aren’t often used in everyday language, so it can be worth knowing how psychologists understand these terms.

Obsessions

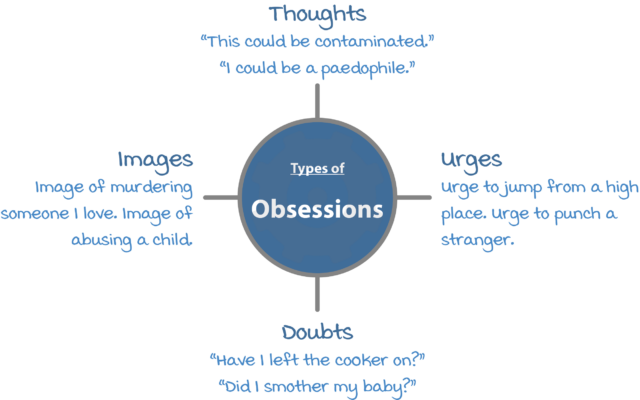

Obsessions are unwanted thoughts, images, urges, or doubts that you find unacceptable, and which make you feel anxious. They are sometimes called ‘intrusive’ thoughts because they pop into your mind – or ‘intrude’ – when you are going about your life. People with OCD find that these thoughts are repeated and persistent, and often scary, unacceptable, or disgusting. Commonly experienced thoughts include:

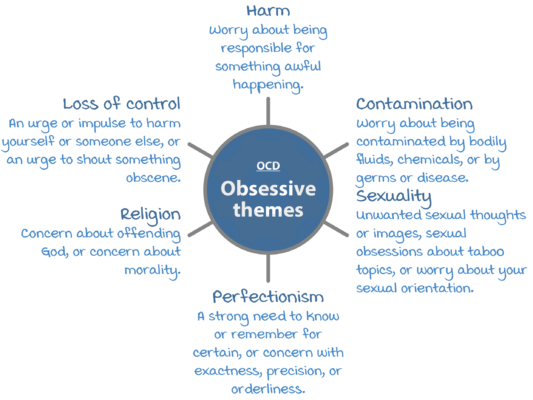

If you have OCD you might have a lot of thoughts like these, but they will often be focused around a particular theme. Some of the most common obsessive themes are:

Compulsions

Compulsions are things that you do, or ways that you react, in response to your obsessions. Your compulsions might be actions, rituals or behaviors that other people can observe, or they might be things that you do secretly in your mind. People with OCD normally use their compulsions either to prevent some harm that they fear might occur, or to relieve a feeling of anxiety or distress. Many people with OCD realize that their compulsions are not rational but feel compelled to carry them out anyway. Examples of common compulsions include:

- Repeated checking. For example, checking that you did not harm yourself or someone else, checking that something terrible did not happen, verifying that you did not make a mistake, checking that you turned the oven off, checking that you locked the door.

- Washing and cleaning. For example, washing your hands until they feel clean, cleaning your house or particular items obsessively, excessive washing or grooming.

- Mental compulsions. For example, praying to prevent harm, ‘canceling’ a bad thought or word with a good one, counting and ending on a ‘right’ or ‘good’ number.

- Repeating. For example, repeating activities, body movements, or mental events.

What is it like to have OCD?

More than many other psychological conditions, the way OCD looks to an outsider can vary a great deal. Monica’s story is just one example of how OCD can affect your life.

Monica’s fear that she would harm her baby

Shortly after my first baby was born, I started worrying that I would harm her. I would have unwanted thoughts and images of smothering or suffocating my baby, and whenever I was in a high place, I would have unwanted thoughts like “what if I threw her off?”. It was horrifying – I thought this meant I was a terrible mother and couldn’t be trusted to be alone with my baby. I tried to push these thoughts away as much as I could. To keep the baby safe, I insisted that my husband be responsible for most of her care. If I couldn’t avoid looking after her, I would pray in my mind the whole time that nothing bad would happen. I didn’t tell anyone about these thoughts in case she was taken away from me.

Do I have OCD?

A diagnosis of OCD should only be made by a mental health professional. However, answering the screening questions below can give you an idea of whether you might find it helpful have a professional assessment.

| Do you have unwanted thoughts, images, or impulses that seem uncontrollable? | |||

| Never | Occasionally | Sometimes | Often |

| Do you try to get rid of these thoughts, images, or impulses? | |||

| Never | Occasionally | Sometimes | Often |

| Do you have rituals or repetitive behaviors that take up a lot of time in a day? | |||

| Never | Occasionally | Sometimes | Often |

| Do you wash or clean a lot? | |||

| Never | Occasionally | Sometimes | Often |

| Do you keep checking things over and over again? | |||

| Never | Occasionally | Sometimes | Often |

| Are you troubled by these problems? | |||

| Not at all | A little bit | Quite a lot | Very |

If you ticked the rightmost box to lots of these questions it is an indication that you could be suffering from OCD.

What causes OCD?

There is no single cause for OCD. You are more likely to experience OCD if you have:

- Assumptions and beliefs that make you more likely to develop OCD.

- Early experiences which made you vulnerable to OCD, or made you feel particularly responsible for preventing bad things from happening.

- Critical incidents such as stresses or challenges which kick-start the OCD.

There may be genes which make you likely to develop emotional problems in general, but no specific genes have been found which make you likely to develop OCD [2].

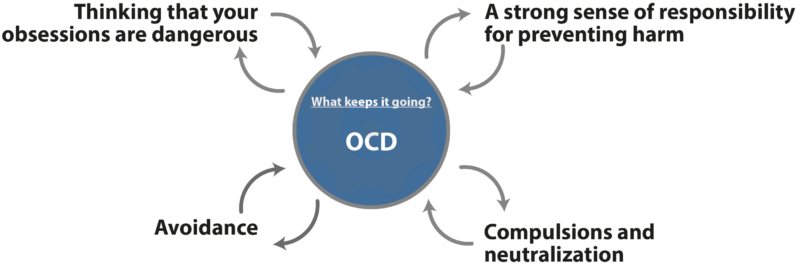

What keeps OCD going?

Research studies have shown that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective psychological therapies for OCD. CBT therapists work a bit like firefighters: while the fire is burning they’re not so interested in what caused it, but are more focused on what is keeping it going, and what they can do to put it out. This is because if they can work out what keeps a problem going, they can treat the problem by ‘removing the fuel’ and interrupting this maintainance cycle.

The important insight of CBT is that the way we feel depends on how we have interpreted what is happening to us. With OCD, this means that the way you interpret your obsessions will affect how you feel, and how you respond to them. Having strong beliefs about being responsible for preventing harm can make you more likely to interpret obsessions in problematic ways. Once you have interpreted particular thoughts as threatening, you are likely to do certain things to keep yourself or others safe[3]. These include:

Treatments for OCD

Psychological treatments for OCD

The most effective psychological treatments for OCD are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and exposure and response prevention (ERP). Specialist guidelines recommend that if you have OCD where the degree of impairment is mild, you should be offered a minimum of 10 hours with a therapist, or longer if the OCD is more severe [4].

CBT is a popular form of talking therapy. CBT therapists understand that what we think and do affects the way we feel. Unlike some other therapies, it is often quite structured. After talking things through so that they can understand your problem, you can expect your therapist to set goals with you so that you both know what you are working towards. At the start of most sessions you will set an agenda together so that you have agreed what that session will concentrate on. OCD specialists have made some recommendations about what high quality CBT for OCD should look like [5]. The most important ‘ingredients’ include:

- Focusing on the OCD problem for most of the time in most of the sessions.

- Working towards collaboratively developed goals which are specific, achievable, and described in terms of what you will do.

- Explaining how your OCD works and what keeps it going (psychologists call this a case conceptualization or case formulation).

- Therapist-aided exposure where you have an opportunity to test some of your beliefs and to face your fears.

- Between-session tasks likely to consist of monitoring, exposure, and behavioral experiments.

- Consistent encouragement to resist your rituals or compulsions.

Medical treatments for OCD

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that medications called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be effective in treating adults with OCD [3].

References

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617-627.

- Mattheisen, M., Samuels, J. F., Wang, Y., Greenberg, B. D., Fyer, A. J., McCracken, J. T., … & Riddle, M. A. (2015). Genome-wide association study in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCGAS. Molecular Psychiatry, 20(3), 337.

- Salkovskis, P. M., Forrester, E., & Richards, C. (1998). Cognitive–behavioural approach to understanding obsessional thinking. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 173(S35), 53-63.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005). Obsessive compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder: treatment. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg31/resources/obsessivecompulsive-disorder-and-body-dysmorphic-disorder-treatment-pdf-975381519301

- Darnley, S., Forrester, E., Heyman, I., Stobie, B., Salkovskis, P, Veale, D. (2019). CBT Checklist for OCD. Retrieved from: https://www.ocdaction.org.uk/support-info/have-i-had-cbt-my-ocd

About this article

This article was written by Dr Matthew Whalley and Dr Hardeep Kaur, both clinical psychologists. It was last reviewed on 2021/12/08.